A New Dimension for Spin Qubits in Diamond

The path toward realizing practical quantum technologies begins with understanding the fundamental physics that govern quantum behavior—and how those phenomena can be harnessed in real materials.

In the lab of Ania Jayich, Bruker Endowed Chair in Science and Engineering, Elings Chair in Quantum Science, and co-director of UC Santa Barbara’s National Science Foundation Quantum Foundry, that material of choice is laboratory-grown diamond.

Working at the intersection of materials science and quantum physics, Jayich and her team explore how engineered defects in diamond—known as spin qubits—can be used for quantum sensing. Among the lab’s standout researchers, Lillian Hughes, who recently earned her Ph.D. and will soon begin postdoctoral work at the California Institute of Technology, has achieved a major advance in this effort.

In a series of three papers co-authored with Jayich—one published in Physical Review X (PRX) in April and the second and third in Nature in October—Hughes demonstrates, for the first time, how not just individual qubits but two-dimensional ensembles of many defects can be arranged and entangled within diamond.

This breakthrough enables the realization of a metrological quantum advantage in the solid state, marking an important step toward the next generation of quantum technologies.

Well-designed defects

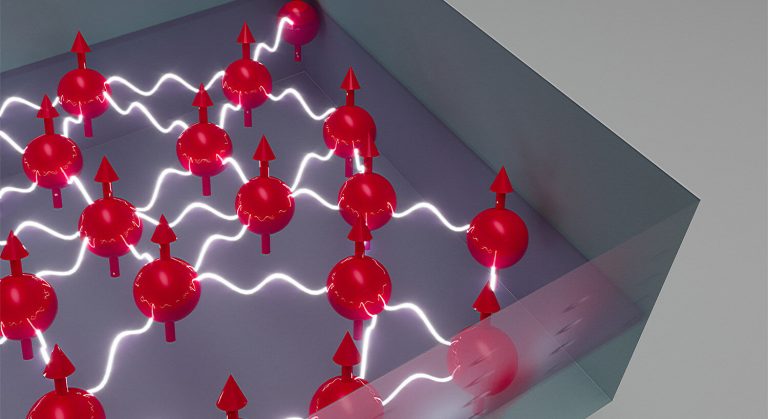

“We can create a configuration of nitrogen-vacancy (NV) center spins in the diamonds with control over their density and dimensionality, such that they are densely packed and depth-confined into a 2D layer,” Hughes said. “And because we can design how the defects are oriented, we can engineer them to exhibit non-zero dipolar interactions.”

This accomplishment was the subject of the PRX paper, titled “A strongly interacting, two-dimensional, dipolar spin ensemble in (111)-oriented diamond.”

The NV center in diamond consists of a nitrogen atom, which substitutes for a carbon atom, and an adjacent, missing carbon atom (the vacancy).

“The NV center defect has a few properties, one of which is a degree of freedom called a spin—a fundamentally quantum mechanical concept. In the case of the NV center, the spin is very long lived,” Jayich said.

“These long-lived spin states make NV centers useful for quantum sensing. The spin couples to the magnetic field that we’re trying to sense.”

The ability to use the spin degree of freedom as a sensor has been around since the 1970s’ invention of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), explained Jayich, noting that the MRI works by manipulating the alignment and energy states of protons and then detecting the signals they emit as they return to equilibrium, creating an image of some part of the internal body.